翁云青作品展映“我的加拿大中国男友”

Wayne Yung retrospective: “My Chinese Canadian Boyfriend”

策展人手记:

翁云青确实算是我的加拿大中国男友。2003年,我在搬到阿姆斯特丹后不久,开始策划我第一个电影节。那时,我遇到了云青。从我们共同的朋友那里,我听说他正住在德国。由于同是旅居欧洲的北美华裔酷儿电影人,他们建议我去见见他。我们在电影节有一段愉快的经历。作为影展组织者,我热情很高却缺乏经验。正是在他的巨大帮助下,我度过了胶带丢失和糟糕字幕的难关。我们很快成了搭档。这些年来,我们想出很多促进欧洲的亚裔和酷儿不再害羞的方式,使他们勇于在银幕上看到自己的面貌,听到自己的声音。亚裔在北美少数族群中以沉默著称,就是所谓的“好学的亚洲移民好孩子”。作为这个群体的成员,我们走上了缓慢而必然的反叛之路。我们从柏林到阿姆斯特丹举行酷儿卡拉OK“偶发艺术”,告诉人们,所有人都可以制作视频并从中得到乐趣,更可以带到酷儿社群的聚会中。同时,云青仍在继续制作视频,讲述他的酷儿、亚裔和现在的欧洲人身份,讲述他的生活。他成为不同国家和身份的融合。正如他过去二十年电影制作生涯,在他的作品中,他一直在创造与自己和与他人的对话,讨论他是谁。云青是酷儿影像艺术的先锋。他一直在大胆探索他的个人生活和空间,并与我们分享他的观念。

An Introduction from the curator:

In a way, Wayne Yung really is my Chinese-Canadian boyfriend. I met Wayne when I curated my first film festival in 2003 shortly after moving to Amsterdam. I had heard of him from mutual friends who knew he was living in Germany and suggested I look him up being both fellow queer North American Chinese expatriate filmmakers living in Europe. We had a blast at the festival as he generously helped guide a very enthusiastic but very inexperienced festival organizer through lost tapes and bad subtitles. We quickly became partners in crime and over the years, brainstormed of ways to radicalize the Asians and Queers in Europe, to not be ashamed to show their faces and hear their own voices and desires on screen and off. As members of the silent model minority in North America, the so-called “good studious immigrant Asian kids”, we slowly but surely became rebels with a cause. We held queer karaoke “happenings” from Berlin to Amsterdam to show that anyone could make a video, have fun doing it and bring the queer community closer together. In the meantime Wayne also continued making videos about his queer, Asian, and now European identity and life as he became a fusion of different cultures and identities. In his work he has always sought to create dialogue with himself and others about who he is as he has always done in his more than 20 year career of making video art. Wayne is one of the pioneers of the queer video art form and continues to bravely explore his personal life and space to bring us the insights of his discoveries.

By Doris Yeung

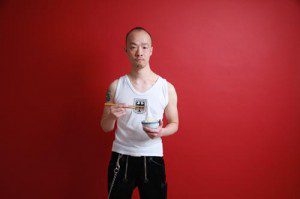

导演简历

翁云青1971年出生在加拿大埃德蒙顿的一个中国移民家庭。他曾经在温哥华、相关、汉堡和科隆生活,目前居住在柏林。作为一个作家、表演者和视频艺术家,他从一个中加酷儿的视角来探索种族与身份的问题。他的第一部录像发表于1994年,他带着自己的作品去世界各地参加放映,包括埃德蒙顿的Latitude 53 Gallery (2008),特拉维夫的LGBT电影节(2008),温哥华的荧幕出柜电影节(2001),首尔的酷儿电影录像节(2000),多伦多的Reel亚洲电影节(1999)。

翁云青将出席影片映后交流,更多信息:www.wayneyung.com

Bio-filmography of Director:

Wayne Yung was born in Edmonton, Canada, in 1971 to a Chinese immigrant family. He has lived in Vancouver, Hong Kong, Hamburg and Cologne, and is currently based in Berlin. As a writer, performer and video artist, he has explored issues of race and identity from a queer Chinese-Canadian perspective. Since his first video release in 1994, he has travelled extensively to screen his work at film festivals around the world, including solo exhibitions at Edmonton’s Latitude 53 Gallery (2008), Tel Aviv’s LGBT Film Festival (2008), Vancouver’s Out on Screen Festival (2001), Seoul’s Queer Film & Video Festival (2000) and Toronto’s Reel Asian Film Festival (1999).

Wayne Yung will be present in Beijing for a Q&A after the screening.

Further information: www.wayneyung.com.

彼得干云青干彼得Peter Fucking Wayne Fucking Peter

加拿大 Canada 1994 4:31

英语对白/中文字幕English with Chinese subtitles

一封酷儿情书,通过用诗歌与性画面来描述不同年龄种族艾滋病感染状况造成的情感张力。

A queer love letter using poetry and sexual imagery to describe the romantic tensions caused by differences in age, race, and HIV status.

搜索引擎Search Engine

加拿大Canada 1999 4:09

英语对白/中文字幕English with Chinese subtitles

亚裔男同通过使用技术来回忆过去的男友,寻找未来的男友。

A gay asian uses technology to remember boyfriends past, in the search for boyfriends future.

怨蓝心曲Davie Street Blues

加拿大Canada 1999 12:35

粤语对白/中文字幕Cantonese with Chinese subtitles

男友离去之后,青年男子迷失在惆怅与抑郁之中,直到一个缄默的街头表演者试图带他走出忧郁。

After his boyfriend leaves, a young man is lost in nostalgia and depression, until a mute streetkid tries to distract him from his melancholy.

西方野花田间指南Field Guide to Western Wildflowers

加拿大Canada 2000 5:33

英语对白/中文字幕English with Chinese subtitles

第一个亚洲之吻:幻想,讨论,实践

The first Asian kiss: fantasizing about it, talking about it, doing it.

心灵旅社My Heart the Travel Agent

Canada/Germany加拿大/德国2002 1:30

关于地铁与异国男友的梦境

A dream about subways and foreign boyfriends.

一千发1000 Cumshots

加拿大/德国Canada/Germany 2003 1:00

关于种族与同性色情作品的闪念

A fast-paced meditation on race and gay pornography.

我的德国男友My German Boyfriend

加拿大/德国Canada/Germany 2004 18:29

英语/德语对白 中文字幕 English/German with Chinese subtitles

一华裔加拿大男同在柏林寻找理想男友时遇到的种族刻板印象

A gay Chinese-Canadian encounters ethnic stereotypes as he seeks his ideal boyfriend in Berlin.

人气小姐Miss Popularity

德国Germany 2006 6:20

英语/德语 中文字幕English/German with Chinese subtitles

一男同志用档案图片来描述他如何应付多重关系的需求

A gay man uses archival footage to describe how he juggles the demands of multiple relationships.

慰藉之窗The Comfort Window

德国Germany 2010 6:34

法语对白/中文字幕French with Chinese subtitles

一年轻男子坦率地说明了他对亚洲男性的渴望

An intimate portrait of a young man speaking candidly about his desire for Asian men.

翁云青访谈An Interview with Wayne Yung:

1) Why is queer Asian identity such a predominant theme in your films?

In Western mainstream media, Asian men have been either underrepresented or misrepresented, even though we represent a very large population in many cities (e.g. Vancouver is almost 20% Chinese); in the gay media of the West, there’s even less people of color. When I began making videos in 1994, there were almost no movies featuring gay Asian men, anywhere in the world. Today there is finally a much bigger variety of queer media being made in Asia, including lots of empowering (and sexy!) images of gay Asian men, and yet this isn’t sufficient for me, because it doesn’t address my concerns as a gay Asian in the West. For example, the subject of racism is very important to me, but it’s probably not much of an issue for a gay director in China, who grew up in a 100% Chinese environment. That’s why I still feel a need to produce my own images of gay Asian men in the Western context.

为什么亚裔酷儿身份是你电影的永恒主题?

在西方主流媒体中,亚洲男人出现得很少,而且常被歪曲。实际上,我们在一些城市中是相当大的群体。比如温哥华20%的人口是华裔。在西方同志媒体中,有色人种就更少了。我从1994年开始制作视频,当时世界几乎没有表现亚裔男同志的电影,如今,终于有了各种在亚洲制作的酷儿作品,包括很多为亚裔男同志赋权的影像。都很性感!但对我来说,情况并不够令人满意,因为它们没有表达一个亚裔男同志在西方生活的心情。种族主义的主题对我来说一直很重要,但对一个生长在中国的同志导演而言,这可能就不那么重要。因此,我需要制作我自己的影像,来表现西方背景下的亚裔同志。

2) Where is home for you?

I’ve been living in Germany for ten years, and now feel very much that Berlin is my home; this is where I have my current projects (and a busy love life!) Recently I was visiting friends and family in Canada, and came to realize that when I feel nostalgic for Canada, it’s not just for the people and the place, but also the era (the 1990s) and life phase (my twenties). So even if I moved back to Vancouver tomorrow, it won’t be anything like what I remember, because the 1990s are long gone, and I’ll never be that young again.

哪里是你的家?

我现在已经在德国住了十年,感觉柏林就是我的家。我在那里做我现在的工作,享受着忙碌的爱情生活。最近我去加拿大看望亲友。我意识到,当我怀念加拿大时,不仅是怀念那里的人和城市,也怀念我生活的那个时代,90年代,怀念我二十几岁的时光。所以,即使我明天就搬回温哥华,那里也不是我记忆中的样子,那个时代已经过去了,我也不可能再年轻。

3) What does the Chinese Diaspora mean to you?

I don’t see it as any kind of unified experience; growing up in Canada is nothing like growing up in Malaysia or the Netherlands or Trinidad, and those who emigrated before the 1960s are quite different from those who emigrated after the 1990s. I feel most closely related to Chinese-Canadians and Chinese-Americans of my generation or earlier. Within this narrower field of the Chinese Diaspora, I do feel very much part of a particular Chinese diasporas experience and culture: we have Chinese parents, and yet grew up in a North American pop culture with particular racial stereotypes, and were also influenced by the experiences of other groups such as blacks, Jews and First Nations people. But when I meet a Chinese who grew up in Berlin, none of these aspects has any significance.

漂浪华人对你而言意味着什么?

我不认为有什么共同的经历。在加拿大长大与在马来西亚或荷兰或特立尼达等地长大完全不同。1960年以前移民过去的人和1990年以后移民过去的人完全不一样。我和年龄相仿的加拿大华人或美国华人更相近些。在这个比较狭窄的范围内,我觉得我们共享一种特殊的漂流华人的经历和文化。我们有华人父母,在北美流行文化中长大,有特定的种族刻板印象,都受到其他种族的影响,比如黑人、犹太人和土著人。但当我遇到在柏林长大的华人时,这些都不一样了。

4) Describe what being Canadian means to you?

For me, it’s simply about having shared a common cultural experience: growing up in a Canadian school system and watching Canadian television (both of which necessitate a working knowledge of the English language), as well as consuming the products found in a Canadian environment, both material and cultural. Even though I no longer live in Canada, I do still feel very much Canadian, as a result of having spent the first thirty years of my life in Canada, and having a personality very much formed by the Canadian context.

作为一个加拿大人对你意味着什么?

对我就是共享一种文化经验。在加拿大学校受教育,看加拿大电视,掌握英语是必要的。还有就是消耗加拿大的环境带来的产品,精神上的和物质上的。虽然我不再住在加拿大,我仍感到自己是个加拿大人,我人生的前三十年都生活在加拿大,在那里形成了我的性格。

5) You have lived in Hong Kong, Canada and Germany. What were your impressions as a queer Chinese-Canadian living in these places and where did you enjoy living the most?

Other queer Chinese-Canadians form the core of my personal “nation/community,” and the largest numbers of such people are to be found in Vancouver and Toronto. When I show my work at a film festival in these cities, where a large part of my audience is other queer Chinese-Canadians, I know that my stories resonate especially well, and do not require the contextualizing explanations that I have to give to a Berlin audience, for example.

你曾经在香港、加拿大和德国生活。作为一个加拿大中国酷儿,你对这些地方有什么印象?你最喜欢住在哪里?

其他加拿大中国酷儿组成了我个人“社区”的核心。他们中的大部分来自温哥华或多伦多。当我在这些城市放映我的作品时,我的故事可以唤起很好的共鸣。如果面对的是柏林观众,我就得对背景进行一番解释。

On the other hand, in Hong Kong I felt very isolated. Part of it was the language: although my parents speak Cantonese, I speak only a little, and can’t really carry a conversation. But a much bigger problem was cultural: even when speaking English with gay Hong Kongers, I found that their concerns were very different from mine, and my political viewpoints were quite alien to them. I was much too Westernized, and had Western expectations of what the gay scene (and the arts scene) should look like.

而在香港我有被隔离的感觉。一方面是因为语言不通,虽然我父母都讲粤语,我却只能说一点点,不足以进行对话。但更大的原因还在于文化。即使与香港酷儿用英语交谈,我们的关注点也非常不同。我的政治观点和他们更是不一样。我太西化了。我对同志场景(艺术场景)的预期都是西化的。

Germany for me is a stimulating balance between the familiar and the foreign. On the one hand, its Western culture makes perfect sense to me (e.g. being engaged in grassroots activism, having a critical stance towards consumerism, placing great emphasis on individuality and personal expression); and yet it’s not North America and it’s not English-speaking, so I’m constantly challenged to look at every issue from a different angle. Although I was quite happy living in Vancouver, moving to Germany was a very fruitful (and necessary) step in my personal and artistic development, and I’m very happy to live in Berlin today.

德国对我来说,在熟悉与陌生间取得了平衡,很令人兴奋。一方面我认同西方文化,比如参与草根活动,对消费主义抱有批判态度,重视个体和个人表达;另一方面,这里不是北美,也不讲英语,所以我能够一直用不同的视角来看待所有问题。虽然我很喜欢住在温哥华,但搬家到柏林,是我个人和艺术发展的重要而必需的一步。我现在住在柏林很愉快。

6) What is your dream story or project to make?

I used to dream about making a narrative feature film, with particular inspiration from the films of Wong Kar-Wai. However, I’ve since decided that it’s better to just continue doing what I’m doing, which is making short videos on a low-budget, so that I can preserve this freedom to do what I like, whenever I like, without having to please a producer or an arts council, and without waiting for the very long process of fundraising. My current projects are all scaled to the time and money that I have at my personal disposal, so that artmaking becomes a natural part of my daily life, and not a constant battle with “the system”.

你的理想故事或作品是什么?

我曾经梦想做一部故事片。王家卫的电影给了我很多灵感。但我还是决定继续我现在的工作,制作低成本短片。这样我能够自由地在任何时候都做我想做的东西,而不用取悦制作人或评委会,也不用花很多时间去筹款。我现在的作品都与我能支配的时间和资金相符,艺术制作成为了我日常生活中的一部分,而不是与“制度”的持久战。